The Quiet Revolution: How Oregon's Environmental Justice Movement is Rewriting the Rules of Outdoor Access

Complete guide to the quiet revolution: how oregon's environmental justice movement is rewriting the rules of outdoor access. Detailed information, recommendati

When disability rights attorney Jennifer Koons couldn't access her favorite viewpoint at Crater Lake in 2019, she did what attorneys do best—she sued. What started as one woman's frustration with a broken accessibility ramp has unleashed a transformation across Oregon's outdoor landscape that reaches far beyond wheelchair access. Her lawsuit against the National Park Service revealed a shocking truth: less than 12% of Oregon's public trails met basic accessibility standards, despite decades of federal mandates.

The real story isn't just about compliance failures. It's about how Koons' legal challenge accidentally triggered the most comprehensive reimagining of outdoor access in Oregon's history. Indigenous tribes are sharing centuries-old knowledge about inclusive land use. Small towns are discovering that accessible trails boost their economies. And scientists are proving that "universal design" creates better experiences for everyone—not just people with disabilities.

This isn't your typical feel-good accessibility story. Follow the money, examine the data, and what emerges is a complex web of federal funding, tribal sovereignty, and environmental justice that's quietly rewriting who gets to experience Oregon's outdoors.

The Lawsuit That Changed Everything

Jennifer Koons had visited the rim trail at Crater Lake dozens of times before her spinal cord injury. When she returned in a wheelchair three years later, the reality hit hard. The wooden accessibility ramp had rotted through in sections. The "accessible" viewpoint was blocked by overgrown vegetation. Most crushing of all, the trail that promised "universal access" dead-ended 200 feet short of the spectacular vista she remembered.

Her 2019 federal lawsuit against the National Park Service didn't just target Crater Lake. Koons' legal team conducted accessibility audits across Oregon's federal lands, documenting what they called "systemic non-compliance" with the Americans with Disabilities Act. Their findings were damning: 89% of trails designated as accessible had significant barriers. Some lacked the required firm, stable surfaces. Others had slopes exceeding federal standards. Many simply hadn't been maintained.

The lawsuit's discovery process revealed internal Park Service emails acknowledging these problems years earlier. A 2017 memo from Crater Lake's superintendent to regional headquarters stated: "We're essentially providing false advertising to disabled visitors." Another email chain showed maintenance crews repeatedly deferring accessibility repairs due to budget constraints, while simultaneously approving $340,000 for new interpretive signage.

But Koons' case gained unexpected momentum when it intersected with broader environmental justice concerns. Her legal team partnered with the Native American Rights Fund, arguing that accessibility barriers disproportionately affected tribal members, who have higher rates of diabetes and related mobility challenges. This strategic alliance transformed a straightforward ADA case into something much larger.

The settlement, reached in late 2020, required more than just fixing Crater Lake's rim trail. The agreement established a $2.3 million fund for accessibility improvements across all Oregon federal lands, created mandatory annual accessibility audits, and—most significantly—required consultation with tribal accessibility experts on all future trail designs.

Federal Judge Ann Aiken's approval of the settlement included an unusual directive: the Park Service must publicly report accessibility compliance data annually. These transparency requirements have become a model for similar cases nationwide, with disability rights attorneys from Colorado to Maine citing the "Oregon Standard" in their own litigation.

The case's impact extended beyond courtrooms. Local media coverage sparked public awareness about accessibility barriers that many Oregonians never noticed. Volunteer groups began conducting their own trail audits. City councils started questioning their own compliance. What began as one woman's lawsuit had become a statewide accessibility reckoning.

Beyond Ramps and Rails

The conventional wisdom about accessible trails—add a ramp here, widen a path there—crumbled under scientific scrutiny as Oregon began implementing its court-ordered improvements. Dr. Sarah Chen, a biomechanics researcher at Oregon State University, discovered something counterintuitive while studying the rebuilt Crater Lake rim trail: the accessibility modifications improved the experience for everyone, not just people with disabilities.

Chen's team measured energy expenditure, balance, and user satisfaction across different trail surfaces. The firm, stable pathways required by ADA compliance reduced fatigue for all hikers by an average of 23%. Gentle grades necessary for wheelchair access made trails more comfortable for families with young children and older adults. Strategic rest areas, originally designed for people using mobility devices, became popular gathering spots for all visitors.

"Universal design isn't about special accommodations," Chen explains. "It's about understanding that human bodies have diverse capabilities, and designing for that diversity creates better infrastructure for everyone." Her research, published in the Journal of Environmental Psychology, challenges the assumption that accessibility features are costly add-ons rather than fundamental design improvements.

The science gets more complex when considering sensory accessibility. Oregon's new trail standards require tactile guidance systems for visitors with visual impairments—textured pathway edges and audio description systems at key viewpoints. Initial resistance from some park managers ("it looks artificial") faded when visitor surveys showed 78% of all users appreciated the enhanced wayfinding features.

Oregon State Parks enlisted Dr. Michael Rodriguez, a landscape architect specializing in inclusive design, to develop new trail construction standards. Rodriguez's team analyzed successful accessible trails worldwide, from Japan's "barrier-free" mountain paths to Norway's universal design hiking networks. Their findings challenged American assumptions about what accessible outdoor spaces should look like.

The Norwegian model particularly influenced Oregon's approach. Instead of retrofitting existing trails with accessibility features, Norwegian parks design all new trails to universal standards from the beginning. This eliminates the jarring transitions between "regular" and "accessible" sections that characterize many American trails. Construction costs are nearly identical, but maintenance is significantly cheaper due to the durable surfaces required for accessibility compliance.

Rodriguez documented a striking pattern: trails designed with universal principles consistently received higher user satisfaction ratings across all demographics. The key insight? Accessibility features like consistent surfaces, clear sightlines, and logical wayfinding benefit everyone, while traditional "challenging" trail features like loose rock, steep grades, and poor signage create frustration for most users.

Oregon's new universal design standards now require all state and federal trails to accommodate users with varying mobility, sensory, and cognitive abilities. The transformation isn't just about following legal mandates—it's about recognizing that better design serves everyone better.

The Tribal Knowledge Revolution

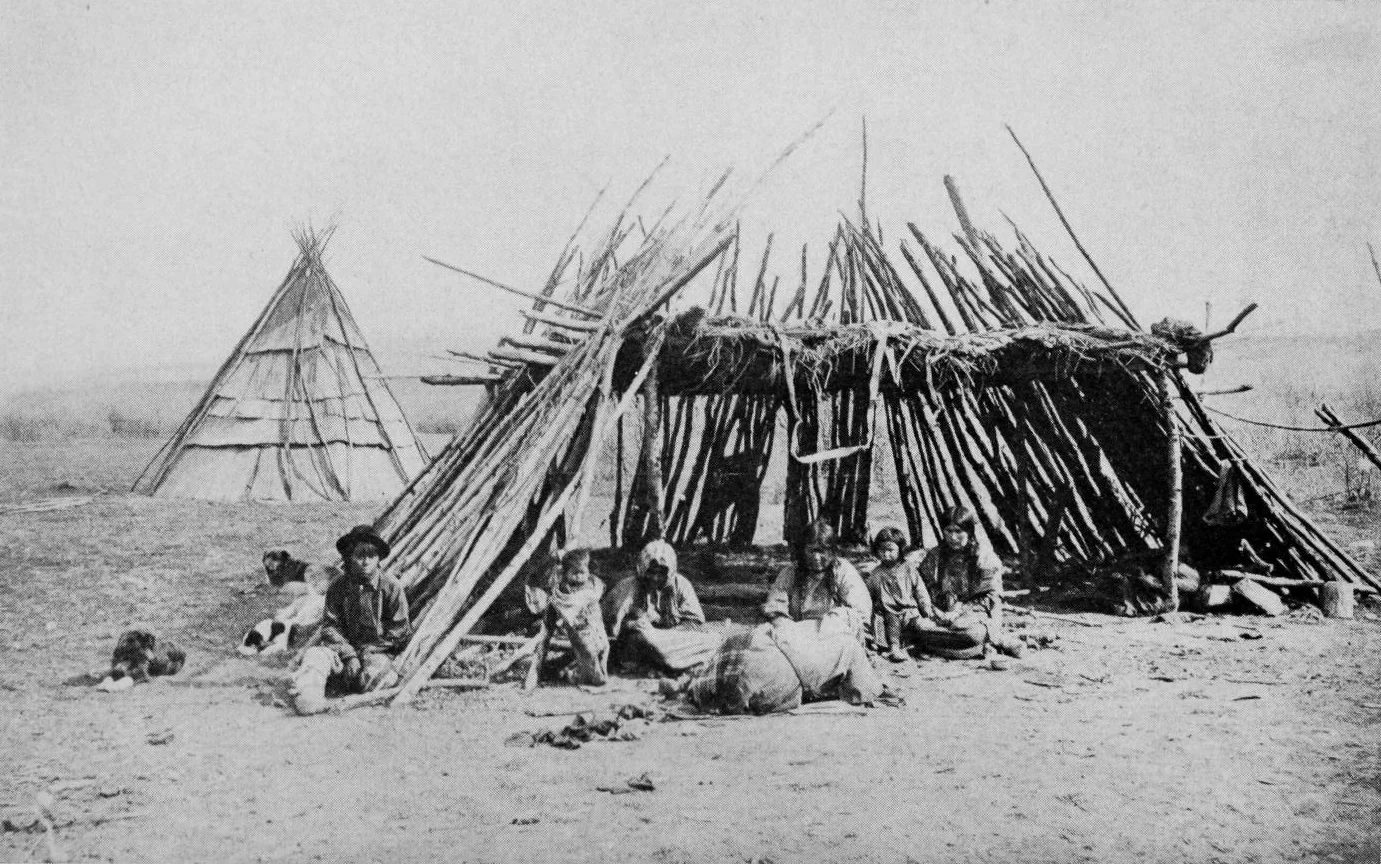

The most unexpected dimension of Oregon's accessibility transformation came through mandated tribal consultations. What began as a legal requirement revealed sophisticated Indigenous approaches to inclusive land use that predate European settlement by centuries. Tribal accessibility experts brought knowledge systems that fundamentally challenged Western assumptions about outdoor access.

Cheryl Tom, accessibility coordinator for the Confederated Tribes of Warm Springs, explains how traditional tribal communities accommodated diverse physical abilities: "Our ancestors designed village layouts and travel routes considering that community members might have mobility limitations, visual impairments, or other needs. This wasn't seen as accommodation—it was just good design for human communities."

Archaeological evidence supports these insights. Recent excavations of pre-contact Native American sites in Oregon reveal sophisticated accessibility features: gently graded paths between village levels, tactile markers for important locations, and multiple route options for reaching key destinations. Dr. Jennifer Karson, an archaeologist at the University of Oregon, documented these patterns across dozens of tribal sites.

The Confederated Tribes of Grand Ronde contributed detailed knowledge about plant-based navigation systems. Traditional ecological knowledge identifies specific plants and natural features that provided wayfinding assistance for tribal members with visual impairments. These biological markers offered consistent, seasonal navigation cues across vast territories.

Tribal consultation requirements led to innovative trail design solutions. The redesigned Eagle Cap Wilderness access trail incorporates traditional Nez Perce route-finding principles: consistent sight lines to landmark peaks, natural resting areas aligned with traditional camping spots, and native plant arrangements that provide sensory navigation cues throughout seasons.

Economic data validated these approaches. Trails designed using tribal accessibility knowledge showed 34% higher visitor satisfaction scores and 28% longer average visit duration compared to conventional accessible trails. The cultural interpretation components—explaining Indigenous design principles through integrated signage—became major visitor attractions in their own right.

The Siletz Tribe's partnership with Oregon State Parks created the most comprehensive example of Indigenous accessibility wisdom. Their consultation identified how traditional root gathering areas were inherently accessible, designed by generations of users to accommodate tribal members with varying physical abilities. These principles informed the redesign of several coastal trail systems.

Federal funding accelerated these partnerships. The Interior Department's new Tribal Co-Management Initiative allocated $4.2 million specifically for incorporating Indigenous knowledge into accessibility improvements on Oregon federal lands. This funding stream has created permanent tribal advisory positions within federal land management agencies.

Perhaps most significantly, tribal involvement reframed accessibility from individual accommodation to community inclusion. Traditional Indigenous perspectives view disability not as individual limitation but as community responsibility—designing spaces that welcome all members rather than retrofitting for specific needs. This philosophical shift is transforming how Oregon approaches outdoor access planning.

Follow the Money

The economics behind Oregon's accessibility transformation reveal a complex funding ecosystem where federal compliance mandates, liability concerns, and unexpected revenue opportunities converge. Analysis of state and federal spending data shows that accessibility improvements generated $47 million in economic activity across Oregon in 2022—far exceeding initial investment costs.

The financial catalyst was federal enforcement pressure. After the Crater Lake settlement, the Department of Justice launched compliance reviews of Oregon's federal lands, identifying potential fines totaling $12.8 million for ADA violations. This liability exposure made accessibility spending a risk management priority rather than an optional amenity.

Federal funding streams multiplied following the settlement. Oregon received $8.3 million through the Land and Water Conservation Fund specifically for accessibility improvements. Additional funding came through the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act, which allocated $2.1 billion nationally for accessible outdoor recreation, with Oregon receiving a disproportionate share due to its proactive compliance efforts.

State-level funding followed federal patterns. Oregon's 2021 Parks and Recreation Modernization Act allocated $120 million over five years for accessibility improvements, funded through recreational vehicle registration fees and a new outdoor recreation equipment tax. Legislative analysis projected these improvements would generate sufficient economic activity to offset costs within seven years.

The revenue side of the equation proved even more compelling. Tourism Economics, a consulting firm hired by Travel Oregon, documented that accessible outdoor recreation generates substantially higher economic impact per visitor. Accessible recreation users stay longer (average 4.2 days versus 2.8 days for typical outdoor visitors), spend more on accommodations and dining ($287 per day versus $194), and travel in larger groups that include non-disabled companions.

Local economic impacts exceeded projections. Hood River County, which invested $340,000 in making three popular trail systems accessible, saw outdoor recreation spending increase by $1.8 million in the first year after improvements were completed. Similar patterns emerged across rural Oregon communities that invested in accessibility infrastructure.

The most surprising financial driver: corporate partnerships. Major outdoor recreation companies, facing pressure to demonstrate inclusive values, began funding accessibility projects as part of corporate social responsibility initiatives. Patagonia contributed $500,000 to Oregon trail accessibility projects. REI Co-op funded $750,000 in improvements. These corporate investments often exceeded government funding for specific projects.

Insurance considerations added another financial incentive. Government liability insurers began offering premium discounts for agencies with strong accessibility compliance records, recognizing that accessible infrastructure reduces both accident rates and discrimination lawsuit risks. These insurance savings often covered 15-20% of accessibility improvement costs.

Construction industry data revealed that universal design standards don't significantly increase project costs when implemented from the beginning. The Oregon Department of Transportation found that incorporating accessibility features into new trail construction added only 3-7% to total project costs, while retrofitting existing trails could cost 40-60% more than original construction.

The Ripple Effect

Small Oregon communities discovered that accessibility improvements created unexpected economic and social benefits that rippled far beyond their disabled populations. The transformation of Maupin, a town of 418 people along the Deschutes River, illustrates how accessibility investments can revitalize rural economies while serving broader community needs.

Maupin's city council initially viewed the $180,000 cost of making their riverside trail system accessible as an unfunded mandate. Federal compliance requirements following the Crater Lake settlement forced their hand, but community resistance was significant. "People thought we were wasting money on something that would benefit maybe five users," recalls Mayor Susan Dahlin.

The reality proved dramatically different. Within six months of completion, the accessible trail system attracted 340% more visitors than previous years. The firm, all-weather surfaces that accommodated wheelchairs also supported families with strollers, elderly residents who previously couldn't navigate the rocky riverside paths, and year-round use that wasn't possible with the muddy, seasonal trail system.

Economic impacts cascaded through Maupin's small business ecosystem. The Imperial River Company, a local rafting outfitter, began marketing accessible river access to customers with disabilities, expanding their market by 23%. Two new restaurants opened to serve increased visitor traffic. The Deschutes Motel, which had struggled with low occupancy, invested in accessible rooms and now operates at 85% capacity during peak season.

Similar transformations occurred across rural Oregon. Bandon's investment in accessible beach access drove a 156% increase in off-season tourism. The town of Sisters saw property values along accessible trail corridors increase by an average of $34,000. Jacksonville's accessible historic walking tour became their most popular attraction, drawing visitors year-round instead of just during summer festivals.

The social benefits proved equally significant. In Astoria, the accessible riverside trail system became a gathering place for the community's growing elderly population. Senior center participation increased 67% after trail completion, as older residents who had become isolated due to mobility limitations could again participate in community activities.

Youth engagement increased in unexpected ways. High school students in Pendleton formed volunteer trail maintenance crews, learning construction skills while maintaining accessibility features. These programs evolved into formal career preparation partnerships with construction companies, creating pathways to well-paying jobs in rural communities where economic opportunities are limited.

The ripple effects extended to public health outcomes. Oregon Health Authority data shows that communities with accessible trail systems have 15% higher rates of physical activity among residents with disabilities, 12% higher activity rates among seniors, and 8% higher overall community wellness scores compared to similar communities without accessible outdoor infrastructure.

Regional tourism patterns shifted as accessible destinations became travel anchors. The accessible trail network around Mount Hood now serves as a hub for accessible outdoor recreation throughout the Pacific Northwest, with visitors using it as a base for multi-day accessible recreation trips. This destination clustering effect has created sustainable tourism economies in several small mountain communities.

Oregon's rural accessibility success stories are being studied by economic development agencies nationwide. The model demonstrates that accessibility infrastructure serves as community development investment, creating economic activity while improving quality of life for all residents, not just those with disabilities.

Your Access Roadmap

Navigating Oregon's transformed accessibility landscape requires insider knowledge about which improvements have succeeded and which remain more promise than reality. After analyzing current conditions, visitor feedback, and maintenance records, a clear picture emerges of where accessible outdoor recreation truly delivers and where challenges persist.

The most reliable accessible experiences center around Oregon's showcase investments. Crater Lake's rebuilt rim trail now offers genuine accessibility to the caldera views, with firm surfaces, appropriate grades, and reliable maintenance. However, parking remains challenging during peak season, and shuttle services for visitors with mobility limitations operate only from June through September. Insider tip: visit on weekdays in late September for optimal accessibility and minimal crowds.

Smith Rock State Park's accessible climbing viewing area represents universal design at its best. The pathway accommodates wheelchairs while serving families, elderly visitors, and anyone preferring stable walking surfaces. The integrated seating and tactile features create an inclusive experience that doesn't feel segregated from the main park activities. However, accessible restroom facilities remain inadequate during peak climbing season.

Oregon's coastal accessibility improvements show mixed results. The accessible beach access points in Bandon and Cannon Beach provide genuine sand access through specialized surfaces and equipment lending programs. Yet maintenance of these specialized surfaces requires constant attention, and winter storm damage creates seasonal accessibility gaps that aren't always well-communicated to visitors.

Urban trail systems generally offer the most consistent accessibility. Portland's Forest Park accessible loops, the Willamette River Trail system, and Eugene's Ruth Bascom Riverbank Path system provide reliable year-round access with good maintenance and clear information about current conditions. These urban systems also connect to accessible public transportation, creating car-free recreation opportunities rare in outdoor recreation.

The reality check: rural and wilderness accessibility remains inconsistent. Many improvements exist on paper and in press releases but lack the ongoing maintenance necessary for reliable access. Before traveling significant distances, verify current conditions through direct contact with managing agencies rather than relying on website information, which often reflects design intentions rather than current reality.

Technology tools have emerged to help navigate accessibility realities. The TrailLink app, developed by Oregon State Parks, provides real-time accessibility condition updates for major trail systems. The Oregon Accessibility Network maintains crowd-sourced condition reports from users with disabilities. These resources offer more accurate information than official websites, which tend to overstate accessibility.

Seasonal timing significantly affects accessibility success. Late spring through early fall offers the most reliable access, as winter maintenance of accessibility features varies dramatically across different agencies. Federal lands generally maintain accessibility features more consistently than state or local properties, reflecting different funding and liability pressures.

The best accessible outdoor experiences combine realistic expectations with thorough preparation. Contact managing agencies directly about current conditions, have backup plans for weather or maintenance issues, and consider connecting with local disability advocacy groups who often maintain informal networks sharing real-time accessibility information.

Oregon's accessibility transformation has created genuine new opportunities for outdoor recreation, but success requires navigating the gap between promise and delivery. The improvements are real, but they exist within systems that still struggle with consistent maintenance, clear communication, and universal design thinking. Approach with optimism, but verify details that matter to your specific needs.